Various anatomical adaptations of the spine between ground and tree dwellers are known from mammals, especially primates. In some cases, the different vertebrae are even associated with certain movement patterns and bodily functions. In a comparative study, two scientists from New York (USA) have now investigated how the spine of ground- and tree-dwelling chameleons differs.

They measured the already existing CT scans on Morphosource.org of a total of 28 chameleons of different species. Brookesia perarmata, Brookesia superciliaris, Brookesia thieli, Palleon nasus, Rhampholeon platyceps, Rhampholeon spectrum, Rieppeleon brevicaudatus and Rieppeleon kerstenii were classified as ground dwellers. Archaius tigris, Bradypodion melanocephalum, Bradypodion pumilum, Bradypodion thamnobates, Calumma amber, Calumma brevicorne, Calumma parsonii, Chamaeleo calyptratus, Chamaeleo gracilis, hamaeleo zeylanicus, Furcifer lateralis, Furcifer pardalis, Furcifer verrucosus, Kinyongia carpenteri, Kinyongia tavetana, Kinyongia xenorhina, Nadzikambia mlanjensis, Trioceros feae, Trioceros jacksonii and Trioceros quadricornis were considered arboreal. The vertebrae were counted and the width of the lamina, length, width, height of the vertebral body, and the height of the spinous process and transverse processes on each vertebra were measured. In addition, the so-called prezygapophysial angle was determined. This is the angle of the intervertebral joint, i.e. the contact surfaces between the individual vertebrae. The measurements of ground and tree dwellers were compared and statistically evaluated. Only the vertebral column of the trunk was considered, the caudal vertebral column was left out.

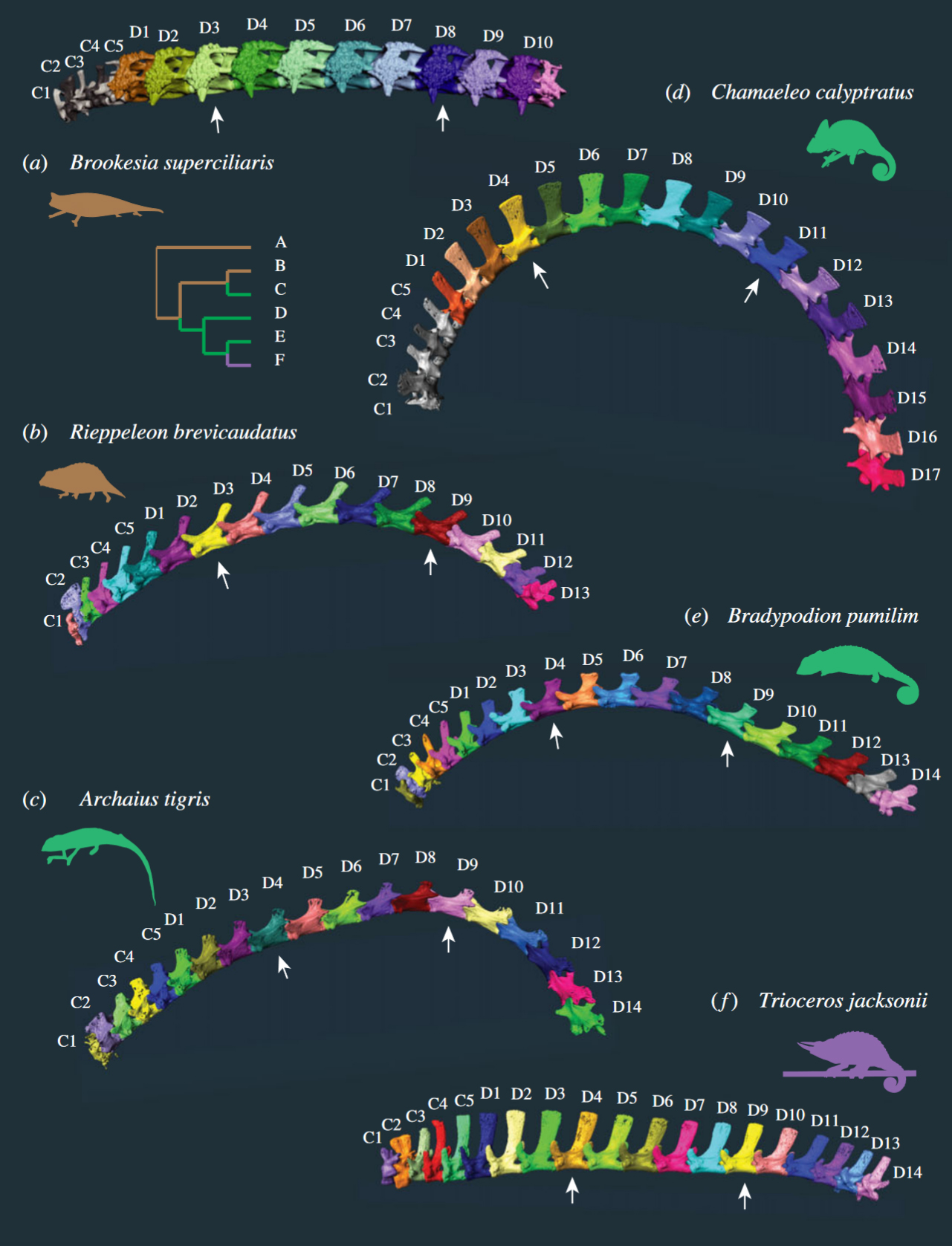

First of all, the results showed that ground-dwelling chameleons generally have fewer trunk vertebrae (15 to 19) than tree-dwelling chameleons (18 to 23). The trunk spine of almost all species could be divided into the already known three areas: Cervical spine and anterior and posterior dorsal spine. A thoracic and lumbar spine as in mammals is generally not distinguished in chameleons because of the continuous ribs. Five chameleon species had four regions instead of three: they had an anterior and a posterior cervical spine, the anterior one consisting of only two vertebrae with rib processes. Six chameleon species had two additional lumbar vertebrae and one species had three transitional vertebrae in the region between the cervical and dorsal spine. In Kinyongia carpenteri, a total of five regions could be distinguished in the trunk spine: The chameleon had anterior and posterior cervical vertebrae as well as anterior and posterior dorsal vertebrae and two additional lumbar vertebrae. Brookesia perarmata was also a special case: the trunk spine of this chameleon consisted of only two regions and at the same time the smallest number of vertebrae of all species studied.

The greatest differences between ground and tree-dwelling chameleons were found in the prezygapophyseal angle (PZA) and the height of the spinous process. The intervertebral joint surfaces in the anterior dorsal vertebrae of tree-dwelling chameleons were clearly more dorsoventrally oriented and smaller than in ground-dwelling species. Several tree-dwellers showed a PZA of less than 90°. In tree-dwelling chameleons, the largest spinous processes were located at the transition from the cervical to the dorsal spine. Among the ground-dwelling species, the spinous processes were similar only in Palleon nasus. In ground-dwelling chameleons, the appearance of the spinous process varied greatly. Rieppeleon, for example, showed narrow, backward-sloping spinous processes, while the spinous processes in Brookesia were more like a kind of bone bridge than a process. Archaius tigris was an exception: The spinous processes in this chameleon hardly differed along the entire spine.

The authors conclude from the results that the anatomy of the different vertebrae is strongly related to the chameleons’ way of life and different locomotion. The intervertebral joint surfaces in tree-dwelling chameleons are probably important for climbing by supporting the function of the shoulder girdle. Reduced mobility in the mediolateral plane provides greater trunk stiffness, which facilitates climbing in arboreal dwellers. Stiffening of the axial skeleton (skull, trunk spine and thorax) is also known from tree-dwelling mammals. The larger spinous processes in larger chameleons could facilitate shoulder girdle rotation and muscle movement, resulting in increased stride length, better head support, and thus possibly easier feeding.

Morphological and functional regionalization of trunk vertebrae as an adaption for arboreal locomotion in chameleons

Julia Molnar, Akinobu Watanabe

Royal Society Open Science 10, 2023: 221509

DOI: 10.1098/rsos.221509

Illustration: Spines of different chameleon species