How do chameleons change when their natural habitat has to make way for human settlements? International scientists recently got to the bottom of this question. They hypothesised that a chameleon living in a suburban area must differ from its forest-dwelling conspecifics in terms of injury frequency, external characteristics and bite force as an expression of changed living conditions.

Between 2020 and 2022, 276 Knysna dwarf chameleons (Bradypodion damaranum) were studied in South Africa. The locations chosen were George and Knysna, two towns located around 60 kilometres apart on the south coast of South Africa. George was founded in 1811 and now has over 220,000 inhabitants, while Knysna was founded in 1825 and currently has just under 76,000 inhabitants, although they live in much less space and are therefore much more densely populated. In both cities, Bradypodion damaranum were caught in urban environments (private gardens, public parks, roadsides), examined and then released. Chameleons were also studied 10 to 12 kilometres away in their natural habitat (temperate forest). The adult chameleons were measured and photographed. The data was analysed and compared using various methods. Wounds, scars and bone fractures visible to the naked eye were counted as injuries. To measure bite force, the animals were each encouraged to bite five times on a special piezoelectric measuring device.

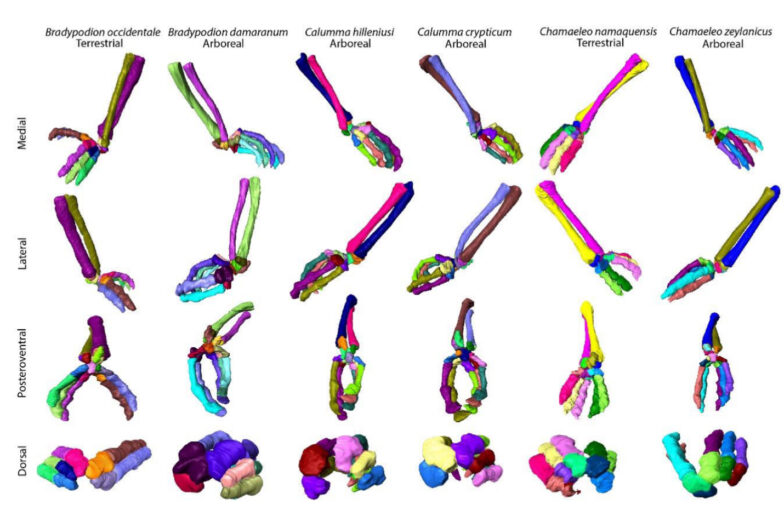

The analysis showed that the dwarf chameleons in urban environments had significantly lower casques and shorter gulars. The males from the city, however, had larger and wider heads. The female dwarf chameleons from the forest had significantly larger casque spurs. The males in the city had significantly more injuries (88.1%) compared to the males in the forest (72.5%). In the city, the dwarf chameleons also bit harder than in the forest when casque height and parietal crest were included in the calculations. However, when snout-vent length was included instead, there was no difference in bite force.

Differences between urban and natural populations of dwarf chameleons (Bradypodion damaranum): a case of urban warfare?

Melissa A. Petford, Anthony Herrel, Graham J. Alexander, Krystal A. Tolley

Urban Ecosystems 2023

DOI: 0.1007/s11252-023-01474-1