It has long been known that chameleons have very special eyes. What is particularly fascinating is that they can move their eyes independently of each other in almost any direction. A team of US scientists has now discovered that the optic nerve in chameleons is also extremely specialised.

They examined adult reptiles of 34 different species using CT models. Brookesia superciliaris, Rieppeleon brevicaudatus and Chamaeleo calyptratus represented the chameleon family. They found that in all three chameleon species, the optic nerve was extremely curled. This anatomical feature means that the optic nerve in chameleons is much longer than would be necessary for an eye looking straight ahead. It probably enables the animals to have extremely mobile eyes without compromising their vision. Put simply, the optic nerve functions a bit like a flexi leash: when the eye moves sharply, part of the optic nerve is ‘unrolled’. When the eye moves back, the optic nerve curls back to its original position without overstretching the nerve fibres.

A new twist in the evolution of chameleons uncovers an extremely specialized optic nerve morphology

Emily Collins, Aaron M. Bauer, Raul E. Diaz Junior, Alexandra Herrera-Martínez, Esteban Lavilla, Edward L. Stanley, Monte L. Thies, Juan D. Daza

Scientific Reports 15, 2025: 38270.

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-20357-3

Download the article for free

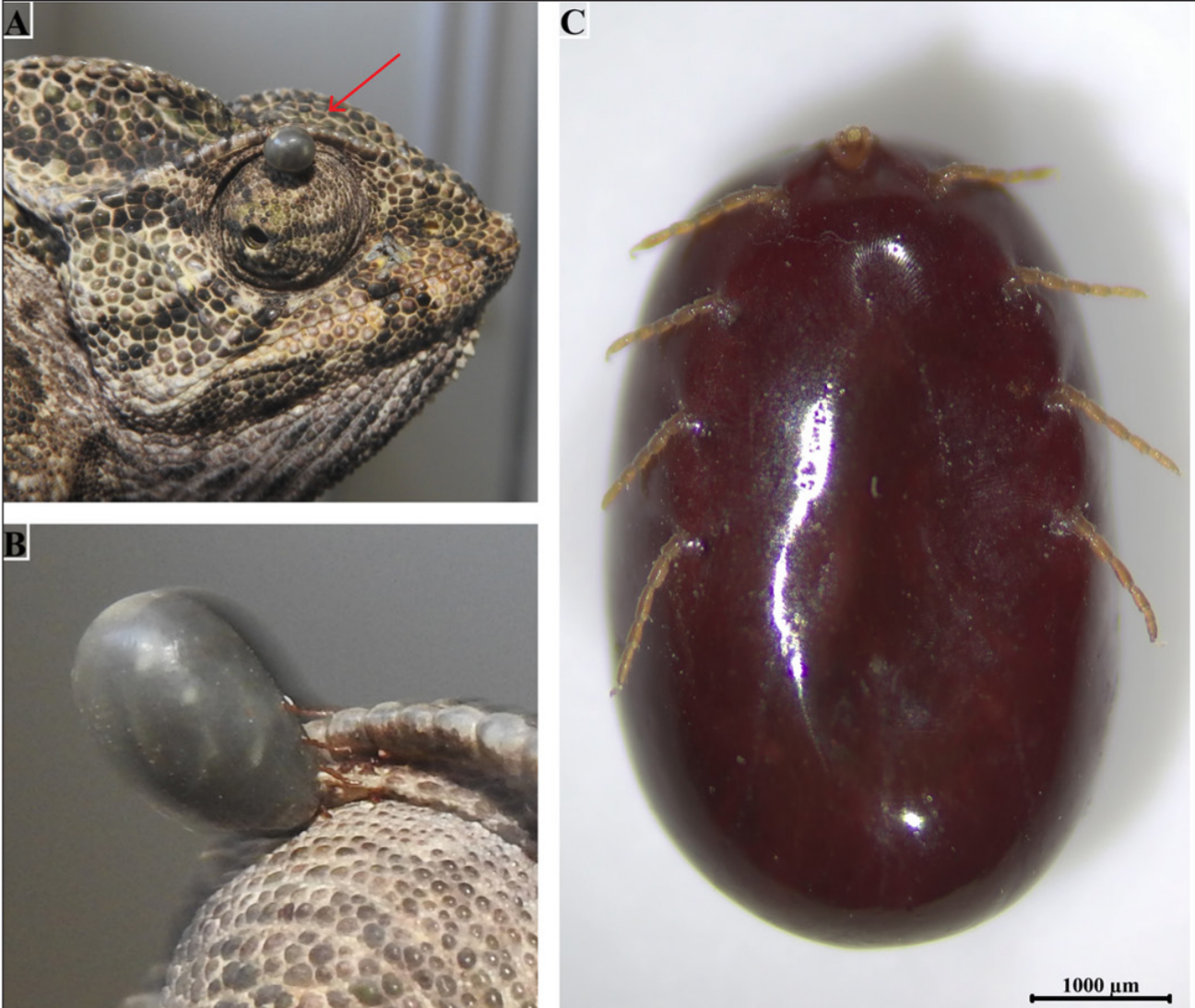

Photo: Portrait of Brookesia superciliaris, photographed by Alex Negro