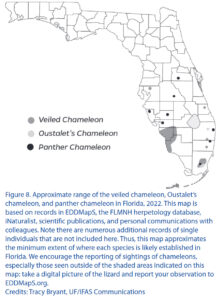

The “Sunshine State” Florida in the USA has the largest number of non-native species of reptiles in the world because of its warm climate. The panther chameleon (Furcifer pardalis) is one of the invasive species, i.e. those that do not actually belong in Florida but are now reproducing there. A study has now investigated the question of what the human inhabitants of Florida actually think of the chameleons.

It has been discussed for a long time whether panther chameleons belong to the species that were deliberately released for the purpose of “ranching”, i.e. to collect the offspring of the released chameleons for sale. That private individuals collect panther chameleons is not in dispute. According to the authors, ranching populations in Florida are mostly kept secret. They became aware of a small population in Orange County via social media in 2019. They then searched for the animals at night with torches and actually found 26 panther chameleons during several walks. They encountered private individuals on several occasions who were also looking for chameleons.

In 2020, questionnaires were distributed in person and via flyers with QR codes to 248 households located within the presumed 0.9 km² distribution area of the panther chameleon population. They were asked about concerns regarding the occurrence of panther chameleons, but also about existing knowledge about invasive species in general. The residents were also divided into three areas: A core region where chameleons had been observed several times, a peripheral region with few findings, and an outer region where no chameleons had been sighted at all.

44 households answered the questionnaire. In fact, all 11 interviewed residents in the outer region had not sighted any chameleons. Of the 33 residents interviewed in the core and peripheral region, about a third said they had already observed panther chameleons. The same number had seen the light of torches at night. 86% of the residents surveyed knew that panther chameleons are not actually native to Florida. Only a few residents said they were concerned about the occurrence. Seven residents had approached collectors with torches and said the collectors had all said they were looking for chameleons for research purposes. Only one of the collectors had said he/she was looking for animals to sell, according to the residents. One resident reported an altercation after strangers entered his property several times looking for chameleons. Another resident called the police because of a whole group of collectors on the neighbouring property.

Unfortunately, the questionnaire was given out after the search efforts of the authors themselves, so it is not apparent from the responses how many of the encounters were indeed with people looking for chameleons for sale purposes. The publication is also a preprint, so no review process has taken place yet.

Colorful lizards and the conflict of collection

Colin M. Goodman, Natalie M. Claunch, Zachary T. Steele, Diane J. Episcopio-Sturgeon, Christina M. Romagosa

Preprint, 2023

DOI: 10.1101/2023.08.10.552819

Picture: Alex Laube