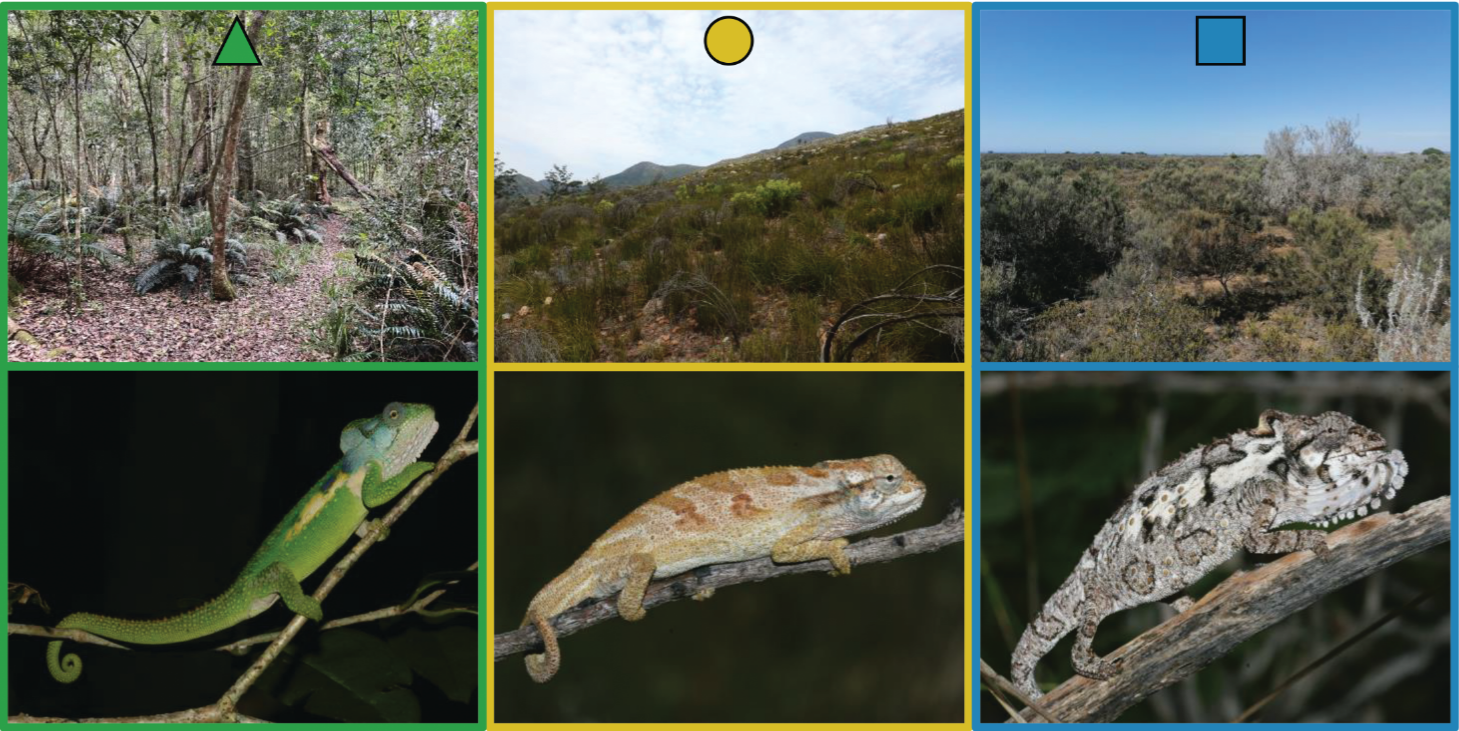

South African scientists have investigated whether the physique of a dwarf chameleon affects the branches it prefers to use. In South Africa, three different ectomorphs, or body types, are known among dwarf chameleons of the genus Bradypodion: First, there is the forest ecomorph. This ecomorph is found in closed canopy forests, is large with a long tail, but relatively gracile. Typical for the forest ecomorph are bright colours and conspicuous gular and and casque ornamentations. The second ecomorph is the ‘small brown chameleon’, which occurs in open habitats such as heathland, grass savannah or fynbos. As the name suggests, this type of chameleon is small, inconspicuous brown or greenish in colour and has reduced gular and casque ornamentation. The third ecomorph is the bushland ecomorph: chameleons in bushland or thickets that are large but generally rather heavy-bodied and short-tailed, rather inconspicuous in colour, but with conspicuous gular and casque ornamentation.

The scientists measured the diameter and angle of the branches used by different Bradypodion species. The following species were among the test subjects: B. barabtulum, B. baviaanense, B. caffrum, B. damaranum, B. ketanicum, B. melanocephalum, B. occidentale, B. pumilum, B. setaroi, B. taeniabronchum, B. thamnobates, B. transvaalense and B. ventrale, as well as the three candidate species ‘emerald’, “groendal” and ‘karkloof’. Chameleons from 38 different populations across South Africa were measured at night and sorted into one of the three body types mentioned above. In addition, branch diameters and angles were measured every 10 metres along randomly selected 100-metre-long transects within a radius of one metre.

The data was then statistically evaluated. Between 2007 and 2024, a total of 1,755 adult Bradypodion and their branches were measured. The forest ecomorph chameleons had access to a much greater variety of suitable branches in terms of diameter and angle than in the other two habitats. The chameleons did not show a preference for certain branches in the forest, but rather ‘used what was available’. The habitat of the ‘small brown chameleons’, on the other hand, had significantly more vertical, thinner branches than the forest, but these had a similar angle. The density of branches was highest in this habitat. However, the ‘small brown chameleons’ chose vertical and usually thicker branches significantly less often than would have been available in their habitat. In the shrubland, the scientists found more vertical and thinner branches than in the forest, and in terms of number, the branches did not differ from the open habitat such as fynbos, but differed in branch diameter. The shrubland ecomorph was larger than those ecomorphs of the other two habitats. It was noticeable that the female shrubland chameleons preferred to use thicker branches and also preferred fewer vertical branches than were available.

The study shows that different ectomorphs of dwarf chameleons in South Africa do indeed occupy different habitat structures.

Comparing perch availability and perch use between African dwarf chameleon (Bradypodion) ecomorphs

Jody M. Barends, Melissa A. Petford, Krystal A. Tolley

Current Zoology 71(5), 2025: 633-644

DOI: 10.1093/cz/zoae076

Free download of the article

Graphic: The three different ecomorphs, from the above-mentioned publication