Rieppeleon brachyurus is a small stump-tailed chameleon species, first described at the end of the 19th century from the Shire Highlands south of Lake Malawi. The species has since been found in Malawi, Tanzania and Mozambique. In Mozambique, it was previously known from rainforests and gallery forests, known as miombo forests. Miombo forests are very open dry forests with sparse grass cover, giving them a savannah-like appearance (hence the term ‘forest savannah’). The Zambezi River, which runs across Mozambique, was previously considered the natural boundary for the occurrence of Rieppeleon brachyurus.

Herpetologists have now discovered that the species also occurs south of the river. They found two juvenile individuals and two adult females of the species in Coutada 11, a 5000 km² hunting concession in the heart of Mozambique. The animals were found there in a sand forest, a rare type of tropical forest on sand dunes, right next to a shallow wetland. These observations extend the previously known range of the species by about 250 km further south.

The authors also report two further new locations where Rieppeleon brachyurus has been found, in Taratibu and Montepuez Rubi Mining Concession, both of which are located north of the Zambezi River. In both observations, the ground chameleons were found in miombo forest at altitudes between 250 and 400 m.

Rieppeleon brachyurus (Günther, 1893) Beardless Pygmy Chameleon First records south of the Zambezi River

W. Conradie, D. Botma, C. Nanvonnamuquitxo

African Herp News 88, 2025: 28-33

DOI: not available

Free download of the article

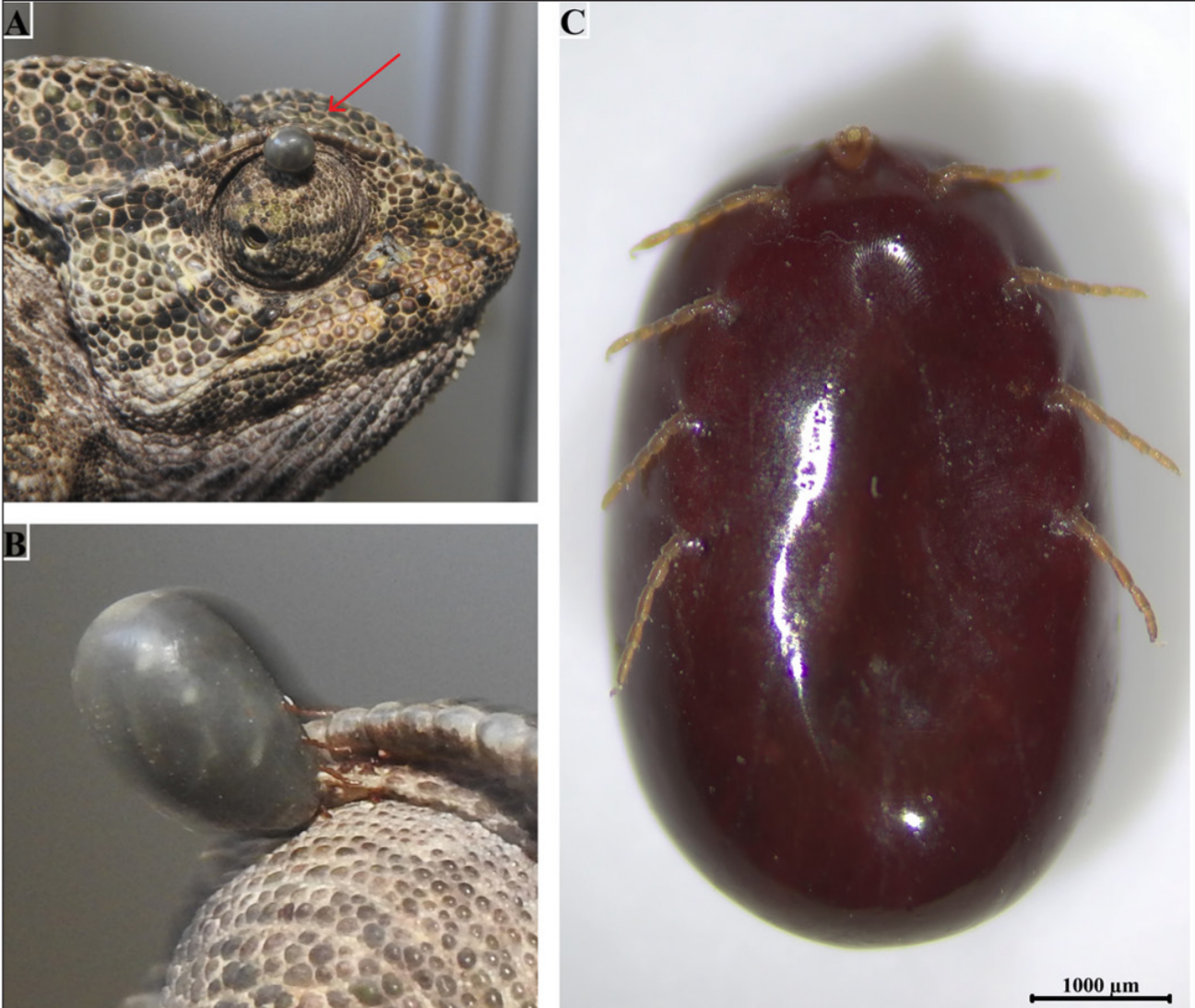

Photo: Juvenile Rieppeleon brachyurus in Mozambique, photographed by Delport Botma, from the above-mentioned publication